The rise of small spacecraft could launch Australia’s space program, writes Steven Tsitas. Australia has long delayed the development of a space program, placing it in an almost unique position amongst comparable countries.But now we can develop extremely small yet powerful low-cost spacecraft, it’s time to reconsider whether Australia should have its own space program.

The future of a sustainable Australian space program — one that actually designs and builds its own spacecraft, and perhaps a small rocket to launch them — is small, lightweight spacecraft using advanced technology with significant two-way US involvement.My research indicates a spacecraft the size of a typical shoe-box weighing just 8 kilograms, known as a 6U CubeSat, can perform some of the missions of much larger ‘microsatellites’ weighing around 100 kilograms – or roughly the size of a washing machine.

This 10-times size reduction should make the cost of producing a spacecraft 10-times cheaper — around $1 million versus $10 million.The cost may now be low enough to make it politically possible for Australia to have a sustainable space program based on this spacecraft.Utilising this technology would provide economic opportunities for Australia, improve our strategic relationship with the US and inspire the next generation of students to study science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Economic opportunities

This is perhaps the last chance for Australia to enter this high growth-rate industry in the capacity of designing and building its own spacecraft.

In terms of economic opportunity, the worldwide space industry has annual revenue of $275 billion and a 9 per cent growth rate. But barriers to entry are high, with established players who are decades along the experience curve — except in the last remaining niche of 8 to 40 kilogram spacecraft.Spacecraft cost their weight in gold despite being made from mostly inexpensive raw materials, indicating significant value is added through design and manufacturing.

Australia has the opportunity to earn significant export income through this technology. A high growth rate industry with the opportunity for significant value addition, such as the early days of the personal computing industry or the internet, is considered a good economic opportunity.The fact that the spacecraft can be designed to perform some of the missions of 100 kilogram microsatellites indicates a level of capability that scientists could exploit by replacing the standard camera payload with an instrument they design.

This in turn could open up a worldwide market, selling spacecraft to scientists (who purchase them with grant money) similar to how scientists buy lab equipment.The small size and ‘mass production’ of the spacecraft (relatively speaking, compared to other spacecraft which are typically highly customised) will provide a relatively cheap way for scientists to fly their experiments in orbital space. There is currently no low-cost way to do this, preventing the exploration of new ideas in a relatively inexpensive and informal fashion, which is the backbone of science.

What is CubeSat, and what could it do?

CubeSats were originally developed in the US for educational purposes with dimensions of only 10 x 10 x 10 cm (called a 1U) and a mass of 1.33 kilograms.

The CubeSat sits in a ‘P-POD’ that looks like a rectangular mailbox, and is attached to the launch adapter connecting a much bigger spacecraft to the rocket launching it. The P-POD is spring loaded to push the CubeSat out once in space. A P-POD can hold three of the 1U CubeSats, and then 2U and 3U CubeSats were developed.

Doubling the size of a 3U CubeSat to 6U leads to a marked increase in this technology’s capabilities.

It could take pictures that, while not as sharp as Google satellite pictures, would be as sharp as some other commercially available satellite pictures such as from the RapidEye spacecraft, in the same five colours of light that are useful for agricultural monitoring. Similar to the RapidEye constellation of microsatellites a constellation of 6U CubeSats could allow daily updates (unlike Google satellite pictures). This could be used to help with agricultural monitoring in the developing world and improve food security.

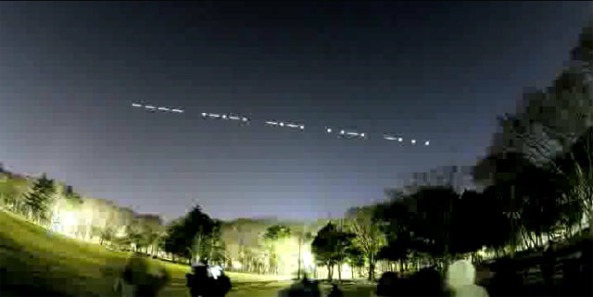

With a different camera the spacecraft could take photos of the Earth at night. Night imaging makes it easier to map the precise extent of human settlement and the data could potentially be sold to government agencies in other countries concerned with mapping human settlement for planning and demographic purposes.

Strategic relationships

Spacecraft are usually so expensive that the technology used in them is quite conservative, to reduce the risk of failure. But a 10-times reduction in cost allows us to risk advanced technologies because failures, if they result, need not be financially crippling, and we gain valuable experience to make these technologies work.

The pay-off is clear: these advanced technologies endow the smaller spacecraft with enough of the capabilities of much larger spacecraft to carry out some of their missions.

The US is interested in this low cost, light weight, high technology approach, as is the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency or DARPA. In particular, its ‘SeeMe’ program is the example that should be followed for an Australian space program, but in a civilian context.

Building up a national capability in small, lightweight (8 to 40 kilograms) advanced technology spacecraft with significant two-way US involvement will allow us to develop a complementary space capability which the US can benefit from.

This is similar to how the US relied on Canada to develop the robotic space arm used on the Space Shuttle. Being a valuable partner in space will improve our strategic relationship with the US.

The rationale for developing this technology would hold true for any country allied with the US, but currently lacking a space program; there is no special reason why it should be Australia that capitalises on this research, other than it is by an Australian.

The economic, strategic and educational rationale for Australia to develop a space program based on the 6U CubeSat does not require that the 6U CubeSats actually be used to observe Australia. The fact that Australia currently receives much satellite data free from other countries does not undermine this argument for an Australian space program. Nor does this argument depend on potential Australian users stating a need for our own satellites.

The radio beeping of Sputnik as it circled the Earth in 1957 galvanized the US into action in space. Hopefully the sound of this opportunity whistling by will stir Australia into the development of a sustainable space program based on the 6U CubeSat.

If Australia fails to grasp this opportunity, others surely will.Source: ABC Science

You must be logged in to post a comment.