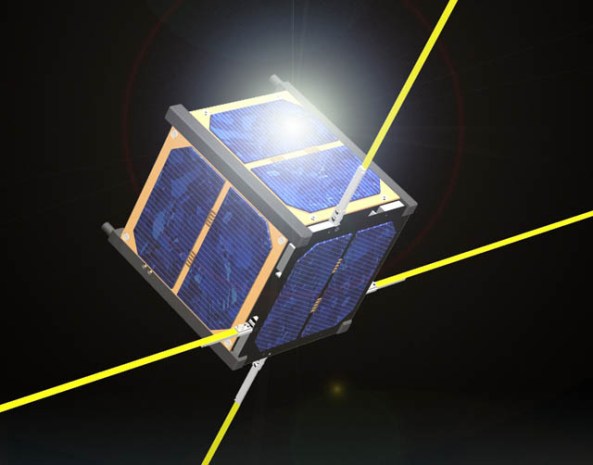

Firefly, a milk-carton-sized satellite, will study gamma-ray bursts that accompany lightning.

Credit: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation

‘CubeSat’ will help solve mysteries of terrestrial gamma ray flashes, 1,000 times more powerful than ‘northern lights’

NSF’s Therese Moretto Jorgensen explains what CubeSats tell us about the atmosphere.

Credit: National Science Foundation

imagine a fully-instrumented satellite the size of a half-gallon milk carton.

Then imagine that milk carton whirling in space, catching never-before-seen glimpses of processes thought to be linked to lightning.

The little satellite that could is a CubeSat called Firefly, and it’s on a countdown to launch next year.

CubeSats, named for the roughly four-inch-cubed dimensions of their basic building elements, are stacked with modern, smartphone-like electronics and tiny scientific instruments.

Built mainly by students and hitching rides into orbit on NASA and U.S. Department of Defense launch vehicles, the small, low-cost satellites recently have been making history. Many herald their successes as a space revolution.

Several CubeSat projects funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) are currently in orbit, making first-of-their-kind experiments in space and providing new measurements that help researchers understand Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Atmospheric scientist Allan Weatherwax of Siena College offers a glimpse inside a CubeSat.

Credit: National Science Foundation

Firefly is designed to help solve the mystery of a phenomenon that’s linked with lightning: terrestrial gamma rays, or TGFs.

Bursts of gamma rays usually occur far out in space, near black holes and other high-energy cosmic phenomena. Scientists were surprised when, in the mid-1990s, they found powerful gamma-ray flashes happening in the skies over Earth.

Powerful natural particle accelerators in the atmosphere are behind the processes that create lightning. TGFs result from this particle acceleration.

Individual particles in a TGF contain a huge amount of energy, sometimes more than 20 mega-electron volts. The aurora borealis, for example, is powered by particles with less than one-thousandth as much energy as a TGF.

But what causes a TGF’s high-energy flashes? Does it trigger lightning–or does lightning trigger it? Could it be responsible for some of the high-energy particles in the Van Allen radiation belts, which can damage satellites?

Firefly soon will be on the job, finding out.

Firefly, as it will look once launched high into the atmosphere above Earth.

Credit: NASA

The CubeSat will look specifically for gamma-ray flashes coming from the atmosphere, not space, conducting the first focused study of TGF activity.

The Firefly team is made up of scientists and students at Siena College in Loudonville, N.Y.; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.; the Universities Space Research Association in Columbia, Md.; the Hawk Institute for Space Science, Pocomoke City, Md.; and the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Princess Anne, Md.

Students are involved in all aspects of the mission, from design and development, through fabrication and testing, to operations and data analysis.

Firefly ‘catching’ a terrestrial gamma ray, or TGF, in action.

Credit: NASA

Firefly will carry a gamma-ray detector along with a suite of instruments to detect lightning, says Therese Moretto Jorgensen, program director in NSF’s Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences, which funds Firefly and its CubeSat companions in space.

The CubeSat will return the first simultaneous measurements of TGFs and lightning.

When thunderstorms happen, powerful electric fields stretch upward for miles, into the upper atmosphere. These electric fields accelerate free electrons, whirling them to speeds that are close to the speed of light.

When these ultra-high-speed electrons collide with molecules in the air, they release high-energy gamma rays as well as more electrons, starting a cascade of electrons and TGFs.”Gamma rays are thought to be emitted by electrons traveling at or near the speed of light when they’re slowed down by interactions with atoms in the upper atmosphere,” says Moretto Jorgensen. “TGFs are among our atmosphere’s most interesting phenomena.”

Atmospheric scientists think TGFs occur more often than anyone realized and are linked with the 60 lightning flashes per second that happen worldwide, says scientist Allan Weatherwax of Siena College, a lead scientist, along with Doug Rowland of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, on the Firefly project.

Build-up of electric charges at the tops of thunderclouds from lightning discharges can create a large electric field between clouds and the ionosphere, the outer layer of Earth’s atmosphere. But how this might lead to TGFs is unknown.

“Firefly will provide the first direct evidence for a relationship between lightning and TGFs,” says Weatherwax. “Identifying the source of terrestrial gamma-ray flashes will be a huge step toward understanding the physics of lightning and its effect on Earth’s atmosphere.”

Unlike lightning, a TGF’s energy is released as invisible gamma rays, not visible light. TGFs therefore don’t produce colorful bursts of light like many lightning-related phenomena. But these unseen eruptions could help explain why brilliant lightning strikes happen.

Following Firefly is FireStation, a set of miniaturized detectors for optical, radio and other lightning measurements.FireStation will fly a bit higher than Firefly.

Its orbit is on the International Space Station.

| Cheryl Dybas, NSF (703) 292-7734 cdybas@nsf.gov |

You must be logged in to post a comment.